How does the anti-vax movement use psychology to endanger public health? Highlighting fear and misinformation behind the Minnesota measles outbreakc

There are a lot of things that make my blood boil, but hurting and deceiving others for profit is near the top of that list. That's why today's topic is about the Minnesota measles outbreak, a sad example of how certain people use psychology to deceive and manipulate others. Once we understand how people use psychology for deception, we can start to spot when others are using our emotions and other psychological tricks to take advantage of us, our friends, and our families.

I don't know if you've heard about the Minnesota measles outbreak yet, but if you haven't, I'll give you a summary. Minnesota is currently experiencing its largest outbreak of measles in decades, with over 60 people infected (mostly unvaccinated children). Measles is a very serious disease that is highly infectious and can be deadly. Luckily, we have a very safe vaccine that prevents people from getting measles, called the MMR vaccine, that also protects against mumps and rubella (other diseases you don't want to get). This video from the CDC shows how measles spread and how the MMR vaccines prevents the spread.

Case closed, you might think. Get the vaccine, and you don't get measles. It should be that simple! However, there is a group of people who are spreading lies about vaccines so that they can profit at the expense of children's health. I am literally shaking right now because it makes me so angry.

I could write a post about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines, but that's been done before. You can find a few here, here, and here.

Instead, I want to talk about why this misinformation spreads, causing many people to get sick with a disease that is preventable through vaccination. How does something so safe and effective get warped for profit? And why do people who are just trying to do the right thing end up believing things that are false -- and even harmful? This is a place where psychology and neuroscience can shed some light on the answers, even if we haven't quite figured out the most effective way to prevent the spread of misinformation (people are REALLY complicated, OK??).

Back to our example of VACCINES:

Vaccines are pretty magical. Scientists work to create medications that are safe, prevent us from getting an illness, and are quick and easy to deliver so that you can give them anywhere -- even in places that are far away with very few resources. A TON of regulation and safety checks go into making vaccines. Scientists and federal agencies like the FDA test these vaccines to make sure they're safe and effective. Then, medical personnel go out into the world to deliver them to people and prevent terrible epidemics! That's a lot of work that goes into this process...but it's totally worth it since it saves MILLIONS of lives per year.

Unfortunately, it only takes one bad person to publicly spread lies about vaccines to make people start to fear them unnecessarily.

Enter Andrew Wakefield. Long story short: he made up data and falsely reported that vaccines were linked to autism. Luckily, he got caught, and his paper was removed from the journal so it couldn't cause any more harm. His medical license was revoked (as it should be). He continues to make a ton of money by going around the world telling parents that vaccines cause autism, which they, of course, do not. THIS MAKES MY BLOOD BOIL. Because of him, a growing number of parents are not vaccinating their child out of fear, and outbreaks are becoming much more common.

Back to the Minnesota outbreak: Wakefield and his fellow anti-vaxxers (a term for people who oppose vaccination) have been going around Minneapolis and lying to parents about vaccines, making them less likely to get their children vaccinated. An interesting fact about the Minnesota case is that the outbreak largely occurred in the Somali immigrant community in Minneapolis. As you can imagine, language, financial, and cultural barriers can make it difficult for immigrants to get access to good health care and can make communication really difficult for parents who are curious to know what's best for their child's health. The Somali immigrants are vulnerable to misinformation because of these barriers, and Wakefield knew that and willingly took advantage of that.

Now, let's get to the science!

What psychological tricks are used to make us believe things, even when they're false?

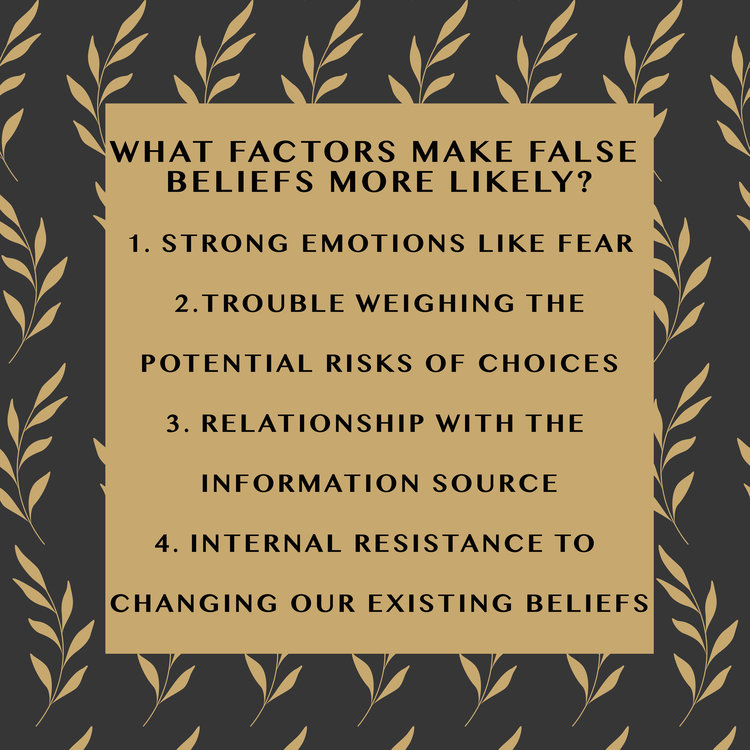

Here are 4 different reasons that we might believe things that aren't true:

1. FEAR

Fear is an EXTREMELY good motivator of our behavior. In general, emotions of all kinds -- sadness, happiness, anger -- are big motivators of our behavior and change the way we think about things. However, FEAR is a powerful emotion because it gets at our most basic survival instincts, and makes parts of our brain that are responsible for avoiding danger very active. For example, if you suddenly see a hungry lion coming at you, your brain detects it and uses your fear to do everything you can to escape that lion. You're no longer thinking about that burger you want for lunch -- you're just trying not to be lunch. In the same way, making people scared is a very good way to get them to focus on your message.

Parents are scared that vaccines will harm their kids, even though all evidence indicates that vaccines are safe, are not linked to developmental problems, and save millions of lives each year from preventable illnesses like polio and measles. BUT there are always people who can profit from planting fear in others, and parents are an obvious target because they care so much about their children’s future. By using lies to plant FEAR in parents, they create a belief that is EXTREMELY hard to change. It’s totally understandable why concerned parents might believe things that are not true if they think they might help their children. However, it’s dangerous when it comes to choices that could seriously harm their children, like the decision not to vaccinate your child.

Fear affects our brain in very real and powerful ways.

Strong emotions like fear also make us more likely to remember things long-term. A part of our brain called the amygdala is very involved in our experience of emotions, and it becomes more active during periods when we have strong emotions, like fear. The amygdala interacts with other parts of the brain to help us store memories of these times in case we need to remember them later. That's why it's usually easier to remember a time you were really scared (remember that lion chasing you?) than it is to remember mundane details like what you ate for lunch last Wednesday.

So when parents hear scary stories from anti-vaxxers, they are probably more likely to remember that story than they are to remember their pediatrician telling them about the safety of vaccines (since that's not a situation that evokes strong emotions like fear).

People use this emotion and memory trick to prey on others. You'll see this with anti-vaxxers, politicians, and people trying to scam you. If they know what we most fear, they can use that info to motivate us to act or believe certain things, even if they're not true!

In addition, we're attuned to pay attention to things that are threatening or scary instead of things that are happy or neutral. We likely evolved that way to scan the environment for threats and keep us safe from harm. However, this might also mean that we're more attuned to threatening information being presented than any other kinds of information!

In sum, our emotions color our daily experiences, and it’s extremely hard to separate our emotions from our thoughts. We are all impacted by our emotions, and we all must work to check our emotions to make sure we're making the best decisions for us, our families, and the world. Recognizing the emotions we attach to our beliefs and trying to figure out how our beliefs developed are SUPER important. We can also use this knowledge about our emotions to spot when someone may be trying to change our emotions to manipulate us into believing something that isn't true.

2. Trouble with weighing risks

Humans have trouble weighing risks of whether something bad will happen based on how often we see the threat in our daily lives. For example, we don't see measles a lot -- fortunately, because of vaccination! -- so we weigh the risk of measles as low even though it can be deadly. For the Somali immigrant community, they were seeing a lot of kids with autism, so they heard the false information about vaccines, they weighed the risk of autism as higher than that of measles. This is also an example of the recency effect, which means that these parents probably saw a child with autism more recently than they saw a case of the measles, so it registered in their minds as less of a threat. They incorrectly judged that the risk of getting measles due to not vaccinating (which is pretty risky, especially in a community with a low vaccination rate) was lower than the risk of getting autism from vaccinating (which, we know, is zero).

That's why we're more likely to fear being a victim of a terrorist attack -- we see them mentioned a lot in the media -- when we're MUCH more likely to die by choking to death (1 in 3,409 for choking vs. 1 in 45,808 for getting killed by a foreign-born terrorist). Dinner doesn't seem to evoke the same kind of fear in us, and choking deaths are not extensively covered by the media.

Our brains can have a hard time using statistics to make decisions if we weigh the risks inaccurately. It's also easier for others to make us fear something that's fresh in our minds and harder to make us fear things that we don't see or aren't exposed to.

3. Your relationship with the information source

Are you more likely to believe a shocking story your best friend told you, or a shocking story that a stranger walked up and told you? If you said the stranger, you may want to reevaluate your friendships. If you said your friend, that's a pretty common answer. We are more likely to trust our friends and identify with them, and thus, we're more likely to believe something they tell us compared to something a stranger tells us-- even if it's somewhat unbelievable. Even if the connection is superficial (e.g., an acquaintance or a friend of a friend), you identify more with that person than you would a stranger.

This phenomenon is known as "ingroup bias" or "ingroup favoritism," which means that we favor people in our ingroup (people we know) vs. our out-group (people we don't know). This effect is very powerful, even if there is no personal connection between members of the group. Even if you are randomly selected to be a part of a certain group (which means you're equally likely to be in this group with ANY person), you're more likely to act in a positive way towards them than you would for those randomly selected into other groups. Because our ingroup bias is so powerful, we're much more likely to remember and believe information that we heard from someone we trust, or even know casually.

So if your friend, acquaintance, or a TV personality that you identify with tells you that he or she thinks that vaccines are dangerous, you're much more likely to believe them than if a random stranger tells you. Because trusted friends and family members in the Somali community were expressing their concerns to each other, parents were more likely to take their advice than they would other health professionals they did not know. This is why it is extremely important to involve trusted community members to convey the truth about how safe and effective vaccines are to concerned parents. Our ingroup bias makes our relationships extremely influential in motivating behavior!

4. Our resistance to changing our beliefs and worldviews

I don't know about you, but I find it a bit frustrating when I find out something new that doesn't fit with how I already think about the world. This happens ALL THE TIME working in science. I predict something will happen based on what we already know, and I do some research to see if I can answer a question about the world. More often than I'd like, I find out that the answer is the opposite of what I'd predicted! It's a pain to have to think about why the world works in a different way than I thought it did. And it's an even bigger pain to incorporate this new knowledge into how I think about the world.

As a scientist, this happens a lot, and I've come to accept it as a challenge of being in science. However, it's usually less hard for a scientist to change their theories about the world because their sense of worth, deeply held beliefs, and emotions are not tied to these theories (not usually at least, but sometimes they are!). However, when you start to think about things that are tied to our self-worth, our purpose, our beliefs, and our emotions (like our forbidden dinner party topics: religion and politics), you can see that it's going to be much harder to convince someone to change their deeply held beliefs!

In fact, many studies have documented how hard it is to change our beliefs, especially if they are important to us.

So what happens if an anti-vaxxer is presented with facts about how safe and effective vaccines are?

You can imagine that someone spreading lies about vaccines has a very strongly held false belief that is likely tied in some way to their identity. If a pediatrician or scientist tells them about the hundreds of studies showing how safe vaccines are, they are going to experience "cognitive dissonance." Cognitive dissonance is psychological stress that happens when you are presented with new information that does not agree with what you already believe.

Instead of reevaluating our deeply held beliefs, we tend to reject any new information that conflicts with what we believe. And if we have motivations to believe a certain thing (to fit in with other parents who believe it, or to keep our identity as an anti-vaxxer) we're even more likely to reject any conflicting information. Instead of critically evaluating the truth of this new information, we might use "motivated reasoning." Instead of thinking about the new information objectively, we are motivated to keep our existing beliefs and we might come up with reasons why the new information is untrue. For example, if a pediatrician tells an anti-vaxxer about the safety of vaccines, the anti-vaxxer might brush off this information by falsely thinking that the pediatrician is being paid to say that by a pharmaceutical company.

As you can see, our motivation to hold onto our deeply held beliefs is extremely strong, and it's easy to see how people can start to reject facts and science once we understand how our beliefs come to be.

Another reason it's so hard to change our beliefs, is that it feels GOOD to hear information that supports what we already think! Feeling like we're right about our belief is rewarding and it's tied to the dopamine system in the brain that processes rewards and pleasure. These rewards makes us feel justified in our convictions and prompt us to want that feeling of reward again.

Once we create a belief, we're also more likely to seek out information that confirms what we already believe and we reject information that says the opposite (termed "confirmation bias"). Why do we tend stick to getting information from sources that confirm our existing beliefs? It feels really good to be validated. It’s totally human to seek out information that is in line with your belief and reject any information to the contrary (even if trustworthy sources like your pediatrician and scientists are telling you the true information).

So once you have a belief, it’s SUPER hard to change it. This is why these lies about vaccines are so easy to spread. Using fear and the other tactics above, you can plant that belief. The hard part is correcting it!

You can also imagine that if it’s closely held belief, or part of your identity is tied to this belief, it's even harder. So a parent who is part of an anti-vaccine group that spreads misinformation is going to be highly committed to their belief, and it's going to be extremely hard to change their opinion.

What's even CRAZIER is that when you present someone who has a strong belief with contrary information, it actually makes them dig their heels in harder about that belief! The more committed we are to an idea, the less likely we will be to change it...so hardcore anti-vaccine advocates are less likely to change their minds because it will cost them more and it will require them to refute many of their old ideas, especially if it's part of their identity. We're more likely to successfully inform people who are undecided or less committed to a belief.

Interestingly, being an educated person doesn't necessarily make you more likely to believe facts. The anti-vaccine movement: there is a significant number of educated parents who don't vaccinate their children. Why? If you think that you're educated enough to do your own research (even if it's flawed) you're more likely to reject science. You're also better able to bend the information you have to serve what you already believe.

How can we use psychology to spread the truth?

One option is to use emotions like fear in a productive way, spreading the truth about the dangers of measles and other preventable diseases. For example, by telling parents the story of a child who suffered greatly with vaccine-preventable illness rather than laying out facts and statistics (which isn't as emotionally compelling), we may be able to use fear in a way that appropriately represents the risks of not vaccinating. Unlike anti-vaxxers, who create fear where no there is no real risk, this method shows parents that this fear of deadly diseases like the measles is what prompted us to create vaccines in the first place. There is also research indicating that informing the public of outbreaks is related to increased vaccination rate the following year. Using the recency effect we discussed above, we can show that these outbreaks are not rare and that they are very real threats to our health and to the health of those who are too young or immunocompromised to be vaccinated!

It’s despicable that people create fear in others to profit, and we need science to help us protect children and families. Let's be vigilant against those trying to manipulate us and keep our minds open to accepting facts!

-Jena

P.S. If you have a little extra time, I really encourage you to read this cartoon from the Oatmeal about how threats to our core beliefs affect our ability to take in new information. It's really well researched and also extremely entertaining!

P.P.S. If you want to read more about vaccine safety and the history of the craziness around vaccines, check out this book below. I added an affiliate link to Amazon but you can also check it out from your local library:

P.S. In case anyone is wondering, I have not been paid by any pharmaceutical company or anyone else to write this post. My only motivation is improving public health. If I can convince even one person that vaccination is safe, or that it's important to examine how others may be planting fears in us to manipulate us, then this post is worth it.